The following article was previously published by Tax Notes, and has been republished here with permission.

An overlooked provision in the Senate-approved infrastructure bill1 would dramatically expand the government’s surveillance of Americans’ economic activity and diminish America’s role in developing an important new technology. The amendment to section 6050I of the tax code should be struck when the bill is taken up in the House. If it’s too late for that, it should be promptly repealed.

Beyond its impact on the liberty and dignity of U.S. citizens, the provision targets a misunderstood set of new technologies — broadly, “digital assets” — and it would damage U.S. leadership in finance and technology.

In a broad range of situations, the proposal would require Americans to collect and report to the government the Social Security number of persons from whom they receive digital forms of monetary value — along with that payer’s name, birth date, address, profession, and reason for the transaction. It does this by adopting wholesale the reporting regime that applies to the in-person receipt of large amounts of physical currency.

The applications and consequences of the proposed law are difficult to summarize, or even to confidently list, because of the mismatch between the new technology being regulated and the old law that is being repurposed to expand government surveillance. This old law concerns the centuries-old technology of physical coin and paper currency, and it primarily governs face-to-face transactions involving more than $10,000 in cash.

The section 6050I proposal would impose onerous surveillance and reporting duties on all Americans, with fines or prison for those who fail (or perhaps are unable) to comply.2 Nominally, the subject of the regulation is “cash,” but it’s not really cash that’s being regulated; it’s people.

Simply put, the new provision has no place in a free society. But in any case, those who would support the new law should be required to argue for it in the cold light of day. A momentous imposition on Americans’ financial affairs — one that will also affect the evolution of a major and still-nascent technology in which the United States may already be losing its leadership role — should not be quietly tucked into a must-pass spending bill under the guise of offsetting a tiny fraction of its trillion-dollar price tag.

A Modest Proposal for Government Surveillance

To appreciate the proposed revision to section 6050I, it helps to take a bird’s-eye view of the government’s initiatives to monitor the flow of money among citizens. The surveillance and reporting of Americans’ financial activity is defended largely as a practical necessity to reduce the underreporting of taxable income and to help fight crime. The status quo has expanded piecemeal over the decades and is spread through different laws and regulations. Critically, most of this surveillance and reporting takes place behind the scenes, beyond the day-to-day experience of most Americans. It has been outsourced to intermediaries such as banks, employers, and the various “brokers” that are defined in terms of their obligation to report third parties’ tax-relevant financial information to the government.3

To understand how the government does, and might, keep tabs on taxpayers in order to maximize its tax receipts, it’s helpful to start with an extreme but hypothetical reporting regime, and then back away to get closer to the present reality. Imagine a very simple system designed to help the government make sure everyone pays their taxes:

Each time any person receives money, the recipient must report the incident to the government.

In this hypothetical system of complete financial surveillance, “any person” means what it says (and includes businesses or other entities). “Receive” means, take possession for any reason. “Report it” means, first, to verify the payer’s name, birth date, address, profession, and Social Security or tax ID number. Then, to promptly send that information — along with the amount received and the reason for the transaction — to the government on a form signed under penalty of perjury.

I hope this proposal strikes you as outrageous, not merely as absurd and impossible to implement as a practical matter. But from here on out, I will focus on the practical implications of the government’s methods of surveillance. The implications for Americans’ rights and interests in living free and private lives are left to the reader.

One reason it would indeed be absurd for the government to demand a report of every monetary transaction is that the government already has pretty good access to much of the data that the hypothetical regime would produce. As we debate how much paperwork and surveillance Americans should tolerate in the name of increased tax revenue, it’s important to be upfront about the status quo. Proponents of new surveillance measures to keep up with technology will argue that the die has already been cast. But when new technologies increase the collateral consequences of more surveillance and reporting, it’s time to ask when enough is enough. Not all measures can be justified by a promise of increased tax receipts, and certainly it is wrong to proceed without informed public debate.

Back to our hypothetical surveillance regime. In light of how things work under the system already in place, it’s not hard to see why reporting every financial transaction is overkill. The government doesn’t need citizens to report every receipt of money because today most money moves through financial intermediaries such as banks. Banks keep good records. They’re required to. They have your name, birth date, address, and tax ID number on file, and your data is linked to every bank transaction you’re involved with. Banks (and other financial intermediaries such as “brokers,” the subject of the separate, much-discussed digital asset reporting provision in the infrastructure bill) are already required to inform the government when something notable happens with money you’re sending or receiving. And even if nothing triggers a reporting requirement, banks are ready to share even your boring data with the government when asked. They’re also free to report anything they deem suspicious, even if they’re not required to.4

So requiring all transactions to be filed with the government is already unnecessary, because much of that is already taken care of by banks. What’s left that might require monitoring?

Most money moves through banks, but not all of it. Physical cash still exists. I can hand you $100 — or even $1 million — without involving a bank. The government does not like this, of course, because it might not learn who received what from whom. So there are rules governing the use of cash. Many Americans don’t know about these rules because, the way the world now works, the rules don’t actually seem to affect their daily lives. Plus, the rules themselves have helped push cash to the fringe of the economy. Americans still use small amounts of cash, and of course the poor and unbanked use cash a lot, but that’s tolerated despite occasional calls to further reduce the use of physical currency to increase surveillance.5

Arguably, and more charitably, the reason many Americans don’t know about the laws regulating their use of physical cash is that those rules were indeed drafted, debated, and enacted following Congress’s respectful study and recognition of how Americans actually live and go about their economic lives as citizens whose prosperity, autonomy, and liberty are the very goals of good government. On this argument, the well-considered cash rules minimize the law’s intrusion on typical taxpayers’ private affairs in a well-struck balance with fighting crime and tax fairness. But no similar argument can be made about the proposed tax provision’s impact on Americans who might use digital assets. There has been no exploration of how this would affect Americans who wish to use digital assets, and there has been no debate.

Cash still exists, but now there is a new way for me to hand you monetary value without involving a bank or other intermediary. For simplicity, and following the proposed tax provisions, we’ll call this technology “digital assets.” The details of this technology are indeed important, and lawmakers especially would do well to better understand them. Unfortunately, what governments understand best about digital assets is the fact that, like a paper $100 bill, I can give you a digital asset without using a bank or other financial institution. And that means that the government might not hear about it.

As we’ll soon see, old rules restricting the use of cash are the foundation for the new proposal to expand economic surveillance and reporting. If all you care about is tracking every taxpayer’s receipt of money, physical cash and digital assets indeed look a lot alike: All you will notice is that, with both forms of monetary value, the government might not learn about it when you receive some.

So governments are inclined to think the use of digital assets, like the use of cash, should be regulated and even discouraged. And indeed, the proposal to amend section 6050I does just that, purporting to treat physical cash and digital assets exactly the same. These short amendments to the tax code literally redefine the “cash” that must be reported to include “any digital representation of value which is recorded on a cryptographically-secured distributed ledger or any similar technology as specified” by the Treasury secretary.6

But physical cash and digital assets aren’t used in the same ways, so the proposal to lump them together under the statute does not treat them (or the humans that use them) the same. One of them is bulky and using it without the help of a regulated financial intermediary typically requires the payer and the recipient to meet face to face. The other is weightless and can zip anywhere in the world in the blink of an eye. Painting them both with the same brush under section 6050I fails to understand or respect how digital assets are (or might be) used and what makes them an innovation to begin with.

In 1970 Congress began to crack down on the use of cash to fight money laundering. The Bank Secrecy Act required banks to report large cash transactions to the Treasury.7 The threshold for reporting was set at $10,000, which would translate to about $65,000 in today’s dollars.

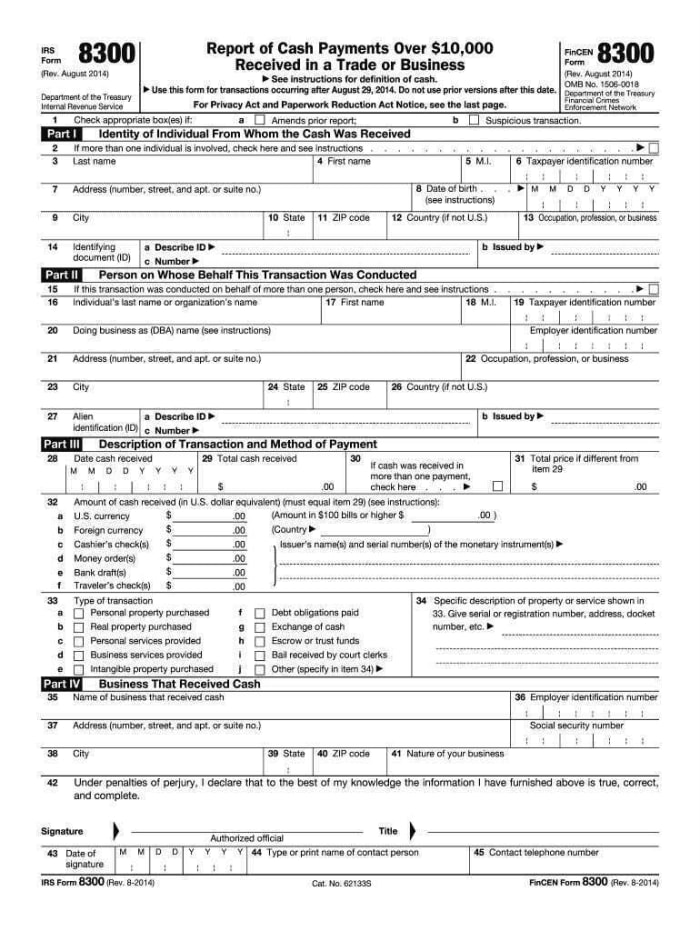

In 1984, this time with the stated goal of increasing tax compliance, Congress added a similar provision to the tax code. Subject to a few limitations, section 6050I requires “any person” who “receives” more than $10,000 in cash in any transaction to report the event to the IRS. This entails filling out Form 8300, signing it, and mailing it to the IRS within 15 days. (Today, there’s an option to file the report online with FinCEN’s Bank Secrecy Act E-Filing system.) The government estimates it takes 21 minutes to fill out a Form 8300.8 Penalties for unreported or misreported Forms 8300 can be as little as $50, for missing the 15-day reporting deadline but curing the mistake within 30 days.9 “Intentional disregard” for the law can result in fines of up to $100,000; willful violations can result in prison time.10 Other penalties apply for failing to send an annual statement by January 31 to each person you reported during the previous year.11

Page 1 of IRS Form 8300, required to be filed when taxpayer receipts trigger the section 6050I reporting requirement.

To complete a Form 8300, the recipient of the cash is required to verify the payer’s identity,12 and must also report the payer’s business or profession and the nature of the transaction. The required information includes the payer’s Social Security or tax ID number. Apparently, requiring the disclosure of one’s Social Security number to one’s counterparty as a condition of transacting more than $10,000 was not something that raised concerns among lawmakers in 1984 when they enacted section 6050I. But at least the requirement was practically feasible, as the exchange of money and personal information was likely face to face. This also made feasible the Treasury’s requirement that, if the payer claims to be an alien, the recipient must “examine such person’s passport, alien identification card, or other official document.”13

The only “persons” exempted from the requirement to file Form 8300 are — wait for it — banks and other financial institutions.14 That does make sense because these institutions already have a similar requirement to report large cash transactions under the Bank Secrecy Act. But this asymmetry leads to an absurdity that highlights the indefensible rush to enact this substantive law as a part of a spending bill.

In late 2020 the Treasury proposed to amend, on an expedited timeline, the Bank Secrecy Act regulations for reporting large cash transactions to include transactions in digital assets.15 Following thousands of public comments on this and other proposed regulations, the proposal was slowed to allow further consideration.

That Treasury provision would apply only to financial institutions, not to the “any person” addressed in the new tax proposal. It’s good that the hasty Treasury proposal was slowed. But the result is that financial institutions would be exempt from section 6050I’s new reporting requirement under existing law, while you and I are not. If the Treasury’s proposal deserved further review before being imposed, then this far broader proposal certainly does.

To require reporting, the receipt of cash must be in the course of the recipient’s trade or business, but this limitation does not provide the safe harbor some might expect. Typically, a “receipt” of money does occur in the course of trade or business. The tax code does not actually define “trade or business,” requiring us to look to case law to determine what gain-seeking activities are adequately considerable, regular, and continuous16 to trigger the statute.

Importantly, the requirement of a “receipt” has nothing to do with taxable income, or even revenue, or even the recipient’s right to keep the money: It’s simply the receipt of cash that triggers the statute. Receiving cash on behalf of someone else requires the recipient to report it.17

The regulations make clear that the meaning of “transaction,” that is, “the underlying event precipitating the payer’s transfer of cash to the recipient,” is extremely broad. Here’s the partial list from the regulation18:

“Transactions include (but are not limited to):

- a sale of goods or services;

- a sale of real property;

- a sale of intangible property;

- a rental of real or personal property;

- an exchange of cash for other cash;

- the establishment or maintenance of or contribution to a custodial, trust, or escrow arrangement;

- a payment of a preexisting debt;

- a conversion of cash to a negotiable instrument;

- a reimbursement for expenses paid;

- or the making or repayment of a loan.”

$10,000 seems like a clear threshold, but what counts as a “transaction” exceeding that figure is more complicated. Related transactions count as a single transaction, as might “connected” transactions if the recipient “knows or has reason to know” that they are connected.19

Payments resulting from a single transaction get added up over time, triggering the reporting requirement once they exceed $10,000. And once those payments again reach $10,000, a new Form 8300 must be filed. “Structuring” transactions in an attempt to avoid the $10,000 threshold can itself be a crime.20

As this overview of section 6050I shows, the use of large amounts of physical cash invites high-stakes questions over exactly what transactions require reporting. Those questions are multiplied when “cash” is extended to “digital assets.” And when filing a Form 8300 is clearly required, the nature of digital asset transactions raises another host of questions over how it would even be possible to comply with the information collection and verification requirements.

It’s not feasible, in this space, to list the range of transactions that would trigger Form 8300 reporting — much less to explore the less-certain cases that will depend on the interpretation of the statute’s terms against a technology that was unimaginable when the statute was written. A few notes will have to suffice. Hopefully the law’s significance is clear enough to justify the time and research needed to expose its full costs and consequences.

Simply buying $10,000 worth of digital assets (in one or more “connected transactions”) could trigger the requirement to fill out a Form 8300. Recall that “an exchange of cash for other cash” counts as a transaction. This means that “an exchange of digital assets for other digital assets” is also reportable, raising further questions about the meaning of the term “digital asset” and the uses of them that might trigger the statute.

Receiving digital assets as repayment of a “loan” would require reporting. Already, digital asset technology enables its owners to lend, lock up, submit to the partial or complete custody of others, and otherwise deploy digital assets in ways that are difficult to analogize to physical cash or even to computerized but bank-centric financial technologies. Recall also that “receipt” has nothing to do with income or revenue, and it is explicitly defined to include “custodial” situations. Assuming there is a “receipt,” the statute further assumes that there is an identifiable party capable of providing — indeed, verifying — a tax ID number and other personal information.

In sum, digital assets are not merely, or even primarily, a substitute for physical cash. They’re a potential alternative to the bank-mediated economic activity that the government now leans on so heavily to enforce its surveillance requirements. Intermediaries like banks didn’t evolve simply to serve governments’ interest in collecting taxes and fighting crime; they evolved to serve humans’ goals in commerce, financial security, and whatever else might contribute to human flourishing. A proposal to thwart technology that might reduce Americans’ — and yes, also the government’s — reliance on such intermediaries to achieve their goals should not be rushed. It requires a full and fair debate — and ultimately a solution that does not unnecessarily sacrifice Americans’ privacy and autonomy in the name of tax collection.

Footnotes

1 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, H.R. 3684 (2021).

2 In comparison, a separate and much-discussed tax provision in the infrastructure bill would require exchanges and other “brokers” involved with digital assets to report their customers’ tax information to the government, a revision of section 6045.

4 Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT Act) Act of 2001, P.L. 107-56, section 314.

5 See, e.g., John Carney and Joshua Zumbrun, “The Plot to Kill the $100 Bill,” The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 16, 2016.

6 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, section 80603(b)(1)(B) and (b)(3).

7 31 U.S.C. section 5313.

8 Instructions to IRS Form 8300.

9 Megan L. Brackney, “When Money Costs Too Much,” CPA Journal, July 2020.

10 Id.

11 Id.

12 Reg. section 1.6050I-1(e)(3)(ii).

13 Id.

15 FinCEN, “Requirements for Certain Transactions Involving Convertible Virtual Currency or Digital Assets,” notice of proposed rulemaking, 85 F.R. 83840 (Dec. 23, 2020).

16 Commissioner v. Groetzinger, 480 U.S. 23 (1987).

17 Reg. section 1.6050I-1(a)(3).

18 Reg. section 1.6050I-1(c)(7).

19 Id.

This is a guest post by Abraham Sutherland. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.

Comments (No)