This article originally appeared in Bitcoin Magazine’s “Censorship Resistant Issue.” To get a copy, visit our store.

The internet loves to trade. Doesn’t matter what. Doesn’t matter why. Doesn’t matter how. Over the last decade, exchange has become a medium through which community is created online. Depop, WallStreetBets, Buying/Selling groups, NFT discords; these are novel online spaces where the line between market and social group is as thin as the member count is large. Through the growth of these exchanges, economies emerge, and with these new economies come new systems of value. Sometimes there is little antagonism between these systems and the larger economies within which they exist. The value of shoes for example, while subject to considerations of hype, narrative and rarity, is still interpreted in relation to money. Sometimes however, the animosity is palpable. Sometimes it’s the point. And sometimes it gets big enough that the world, whether it wants to or not, is forced to contend with it.

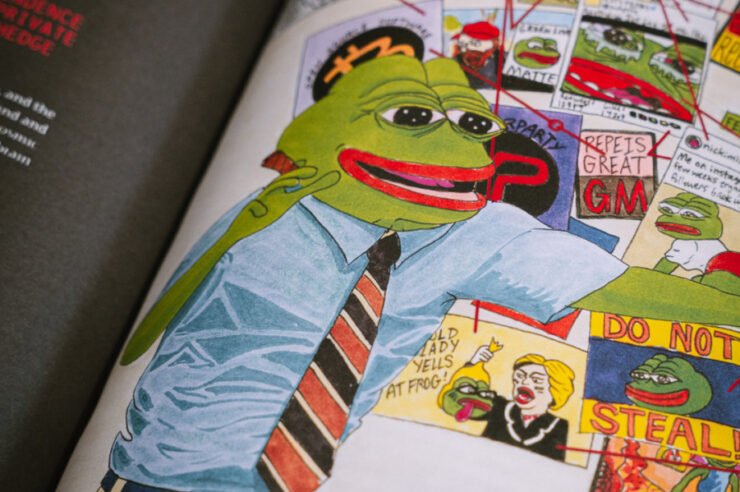

If Bitcoin is one of those latter economies, Pepe, the cartoon frog meme, is as well. Over the course of the past fifteen years, both have experienced massive growth and market-threatening bubbles, idealistic evangelists and profit-maximizing speculators, malicious actors and dedicated communities. What connects them, aside from the assorted projects in which the Pepe economy sometimes finds a home, is the resonance their stories share and the means by which they mean something. Pepe and Bitcoin both represent systems of value forged in stark opposition to the one surrounding them, and both protect that value through a mutually reinforcing consensus of its worth. But while the economic origins of Bitcoin need little explanation, the development of Pepe from meme to commodity and back again requires a bit more to picture. To understand how Pepe became valuable, it’s useful to understand why many thought he should not have been.

In 2014, Pepe was bigger than ever. Pictures of the frog were inescapable across almost every corner of the internet. His Tumblr tag was blowing up, Facebook meme pages were posting him left and right and KnowYourMeme had been covering him for almost half a decade. Pepe, this cartoon frog ripped from a comic book from a decade ago, had taken over the web. As with most memes, Pepe was for many people a way to have some lighthearted fun sharing and laughing at the plethora of his variations with their friends. Others, however, were not happy.

Before going mainstream, Pepe had gotten his memetic start on the cultural fringes of the internet. It started in early 2008, when a scan of Matt Furie’s comic book “Boys Club” from three years prior was uploaded to 4chan’s popular /b/ board and the forums of “Something Awful.” The page features Pepe, one of the four main characters in “Boys Club,” pulling his pants all the way down to pee. When his friend Landwolf asks him why he does that, Pepe responds with quirky and self-assured charm; “feels good man.”

Pepe soon became a fixture in these communities, his variations and visage becoming commonplace. Found a dollar on the street? Feels good man. Didn’t get the job? Feels bad man. He was the perfect reaction image; a genre of meme that lives and dies on its ability to accurately reflect the feelings of the user posting it. Not only was he simple and authentic, but the two constituent parts of Pepe as a meme — his face and his catchphrase — could always individually stand in for the whole. No matter where you were on the internet, no matter what medium you were restricted to posting in, you would be able to give other people insight into how you felt by means of a reference to the funny internet frog. His early mention on BitcoinTalk is a great example of this.

But versatility is not the same as ubiquity, and Pepe’s development as a reaction image was therefore subject to what his original user base was reacting to. Individually, this is impossible to do, but if we’re thinking about the general nature of such reactions on a scale large enough to create meaning, we’re asking about the conditions of a class.

The problem in 2014 was that Pepe was being overused in platforms dominated by normies, whereas he originated in communities predominantly populated by NEETs. NEET is a socioeconomic acronym-turned-identifier which stands for “Not in Education, Employment, or Training.” NEETs are typically 18-35, somewhat adrift in life and — not generally, but certainly within the communities that use the term — mainly male. Alternatively stated, they’re the demographic of the characters in “Boys Club.” Not everybody on 4chan is a NEET, but many are, and even those that are not will pretend to be. “It’s very easy to LARP as this sort of collective,” Brandon Wink, Editor-In-Chief of KnowYourMeme explained. “Yeah, we all live in the basement. Yeah, we’re all this exact same person […] It just makes communication and having a fun time easier.”

NEETs, and thus Pepe’s original user base, are a class distinctly outside of the traditional economy. They neither participate in the production of its goods and services (employment), nor are they on a path to do so (education and training). They still must live in it of course, but they do so begrudgingly. The communities they congregated on, 4chan and Something Awful, can be considered NEETs in their own right. They barely made any money, work on the sites beyond just keeping them running was rare and the teams behind them were relatively insular. Pepe was a symbol of these types of users on these types of communities as the dominant internal reflection of the way they interacted with the world; to see him creep into the mainstream was to see that significance perverted.

Pepe’s normification is his commodification. Normie platforms, aside from being more popular, are also the ones that have a profit motive. Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, etc. These are algorithm-driven feeds where engagement is synonymous with value. The popularity of a post is therefore not an end in itself; the collective relatability or enjoyment is merely a means to more impressions and thus more money for the hosting company. Celebrities with huge industries behind them were posting him, mainstream meme pages driven by huge organic growth and sponsored posts plastered him everywhere. The twist of the knife was that Pepe was now a reaction image, employed to describe social and cultural conditions that were not positioned as the outsiders. “This was Pepe misinterpreted,” one timeline of Pepe uploaded to imgur lamented, “this was Pepe with friends.” Pepe, a NEET, had been conscripted into being an active participant in the very milieu that was so hostile to his origins.

Earlier we spoke about the two resonances between Pepe and Bitcoin; the motivation behind their economies and the consensus that keeps them stable. The two reactions to Pepe’s normification, and their ensuing fallout, also happen to illustrate these two connections, albeit at different points in their development.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Bitcoin emerged as an alternative to centralized banking. The stewards of capital, it was argued, were in no position to hold such power, and as such a new decentralized economy had to be formed. This is no simple task, as getting everyone to buy into and participate in this new economic regime required them to take a leap of faith; they needed to see Bitcoin, a network protocol of distributed math on the internet, as inherently valuable.

Pepe needed no such leap. In October of 2014, 4chan users began to post Pepes with watermarks saying “Rare Pepe – Do Not Steal” or similar messages as a tongue-in-cheek way of combating the spread of their memes to other platforms. As this went on, a LARP-y pseudoeconomy developed. Different users would create Rare Pepes and offer them up for sale or exchange to other users. Pepe for Pepe, Pepe for Good Boy Points, Pepe for tendies, etc. The currency was fake, but the symbolic value was real. The normies could have the normie Pepes, fine, but everyone knew the Pepes that were really worth something were the ones that were less common and accessible. Having a collection of Rare Pepes meant you had been around the places where they appeared, and trading them meant that you were part of the group that knew what the important ones really were. Just like Bitcoin, Wink told me, the practice of exchange was intimately tied up with the definition of its surrounding community. And, like Bitcoin, Rare Pepes quickly found that their abstract communal value was finding footholds in the real world.

This was retaliation by recommodification and a fixing of the record of Pepe’s worth on their own terms. This economy, which for all intents and purposes started as a bit, found more and more people committed to it; eventually indistinguishable from a real economy. As one Reddit user put it; first its funny to trade Rare Pepes for internet points, then it’s funny to trade Rare Pepes for a couple dollars, then it’s funny that a folder of Rare Pepes is driving bids upwards of $90,000 on an eBay auction, then it’s funny that people are trading thousands of them on the blockchain. “You normies took our whole meme and only draw value from an incremental engagement boost? Hold my jpeg.”

There are, however, two ways to change the way a commodity is valued; usurp the current method of extracting value with a greater one or create such conditions as to devalue it altogether. While 4chan’s /r9k/ board was busy swapping Rare Pepes for tendies and memeing themselves into some paychecks, the reactionary-dominant /pol/ board had another idea; make Pepe untouchable.

If you want normies to stop using Pepe, simply make him as obscene a symbol as possible until they stop using him. While /pol/ started with an attempt to associate him with excessively cringe toilet humor (e.g., quite literally memes along the lines of “Pepe PeePee PooPoo”) things quickly took a turn for the fascistic. Images of Pepe with offensive slurs, racist caricatures, and swastikas circulated around the board and through other hotbeds of the newly emerging online political faction soon to be dubbed the Alt-Right. As intentional poison-pills, these images were spread onto larger platforms and slowly inflected Pepe’s broader image with the knowledge that there was a group that was beginning to use him as a dog whistle. This was a distinctly more directed effort in comparison to what some shitposters referred to as the “circlejerk” nature of Rare Pepes. According to Arthur Jones, director of the Pepe documentary “Feels Good Man,” the intention was specifically to invoke a feeling of “satanic panic” — to make Pepe so abhorrent that any sight of him was always a sign of something much more sinister.

This effort was effective, and culminated with the Anti-Defamation League declaring Pepe a hate symbol in late September 2016. For the trolls, this was a huge win in what they narrativized at the time as “The Great Meme War.” For others, it was a loss. “It kind of sucked,” said Shawn Leary, one of the “Rare Pepe Scientists” behind the Bitcoin-based Pepe trading platform Rare Pepe Wallet, “we put all this work into this thing and then it became this political football […] I didn’t want to tweet about it. Who wants to be called a racist even though it was all Safe For Work?” Adding yet another layer of irony to the story of Pepe, it seemed like his existence for some of his most dedicated followers was being put at risk by the campaign of a cohort theoretically on the same side of their battle. The censorship was coming from inside the house.

There was a third group though, and it was the biggest one. Their reaction was characterized not by enthusiasm nor dismay, but a lack of one altogether. Recounting his experience talking to teenagers at a March For Our Lives rally in Washington, D.C., Jones noted his surprise at the fact that none of them had even registered Pepe as a hate symbol. “They liked him because he was a sad frog,” Jones explained, “and they viewed him as a slightly washed meme at that point.”

For all its sound and fury, there are few forces on the internet more powerful than indifference. The attitude of “let the normies have their Pepes” goes both ways. God forbid the edgelords are being edgy with the frog. At the end of the day, Pepe is a meme, memes are open-source and that constitutes a protective measure. There’s a palpable irony to any attempt to gatekeep Pepe. Normies were using Pepe, Pepe underwent a campaign to be turned into a hate symbol, that campaign was effective — and then what? Then nothing. They were successful in the moment but there was still the vast majority of your regular internet content consumers that (a) never really thought of him as a hate symbol, (b) never had a vested interest in protecting him and (c) still like him generically as a meme. Teenagers on the internet are not overwhelmingly on chan-boards, and they probably don’t know what the ADL is. Slowly, another reclamation happened, this time with no battle declared; over time, an understanding grew that all of the attempts to derail him had almost nothing to do with the meme itself.

This is the second and more abstract link between Pepe and Bitcoin; this safety in consensus. Nodes in the blockchain submit their work to other nodes to have it checked and verified, and are granted the ability to add transactions to it. It is possible to try to submit a different result, to try to get access to that ability to become the next source of truth through an answer other than the correct one, but the result will inevitably fail; if nobody agrees with your submission, the transactions and meanings that come along with it are irrelevant.

In flashes, small but dedicated groups have attempted to take control over the latest meaning of Pepe. Realistically though, Pepe has a level of ubiquity on the internet that protects him. The consensus is that he’s the funny internet frog, the guy in monkaS, Feels Good Man etc., and the internet as a whole is much greater in numbers and much healthier in longevity than any of its flashpoint subcultures. He can — and has been — pulled in many directions, but the hash power of the internet as a whole is much larger than any one node trying to take control. Pepe is a symbol of value, a story of community and a reflection of the multiple layers and timelines of the internet. Most of all, he’s here to stay. He’s the internet frog, whatever that means to you. Feels good man.

Comments (No)