Quantitative easing (QE) is a term used to describe when the Federal Reserve buys assets from private markets. Typically, the Fed purchases longer-dated bonds, including Treasury notes and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), but during the pandemic, it has even purchased corporate junk bonds. It does this for a variety of reasons, including (but not limited to) lowering interest rates, liquifying the banking system, ensuring proper functioning markets, and inducing a wealth effect. Academics and market participants have debated both the merits and effectiveness of QE since the Global Financial Crisis. Whether one believes in the effectiveness of QE or not, the goal is ultimately to support aggregate demand in the economy, which is a fancy way of saying they want Americans to spend more money. What I argue here is that Fed purchases of bitcoin could be an effective means to boost aggregate demand and have other benefits as well.

To understand why, we need to briefly explore how QE works and why purchases of some assets are more effective than others. Let’s start with a thought experiment: assume the Fed purchases a three-month Treasury bill from a private market actor. In exchange, the private market actor, through the magic of primary dealers and the banking system, receives a deposit to their bank account, which we think of as money. Then assume the market actor takes said deposit and, to achieve a higher interest rate, converts their deposit to a certificate of deposit. What has changed? I’d argue, hardly anything. All that’s been done is the trade of a liability of the U.S. government for a liability of a commercial bank. That CD in the bank may show up as M2 in fancy graphs, but in reality, the asset transformation has done nearly zilch for the real economy.

Now let’s say the private market actor held a mortgage-backed security with an average term of 10 years. In this case, the Fed has removed two risks from private markets, default risk for the security and duration risk (which reflects that rates could change and the bond could be worth less, if exchanged before maturity). Now let’s assume that, when the Fed bought that MBS, there was no market for them, like during the Global Financial Crisis. Then effectively, the Fed has created helicopter money. It took an asset that was worth 50 cents on the dollar in private markets, and given that market participant par value, i.e., the whole dollar! In doing so, it has lowered long-term interest rates and prevented financial markets from collapsing by removing private market risk. Lowering rates induces price increases in risk assets (wealth effects in commodities, bonds, real estate, and stocks) and preventing market collapse gives people the confidence to spend, not hoard, dollars.

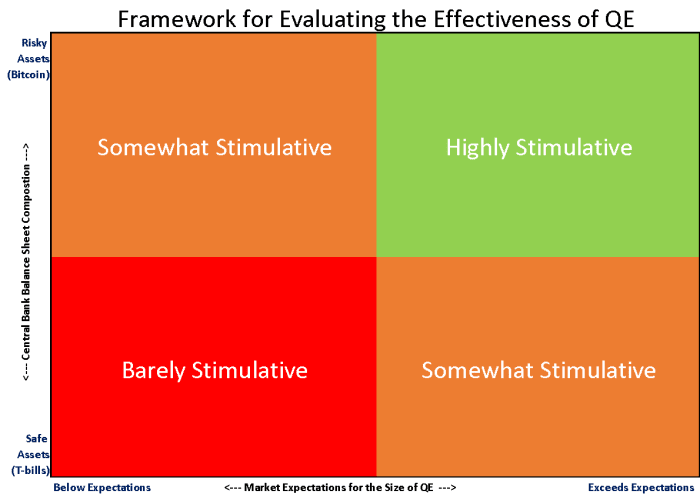

So what can we determine from these two examples? Generally, the more risky the assets the Fed purchases, the greater the effect of that QE, per dollar invested. This is why the Bank of Japan moved QE from only purchases of government bonds, to corporate bonds and stocks. It’s also why some contend that continued QE in healthy markets has diminishing returns for the real economy. Ignoring the slight effects of interest rates, swapping safe government bonds for bank deposits is like giving your kid one hundred $1 bills for a $100 bank CD earning a paltry 0.1%. They’re more liquid, but still have roughly the same net worth. To really juice spending per dollar of QE, the Fed would do best to purchase the riskiest asset it could find (like in the junky MBS example). My conceptual framework for evaluating the effectiveness of QE is provided below:

I know this will upset some Bitcoiners, but truth be told, bitcoin is still a highly risky asset. It could be a safe asset someday, but right now, its volatility will make even the most seasoned investor occasionally pee their pants. I think all Bitcoiners would agree that the Fed purchasing Bitcoin would have a rocket-ship effect on its price. According to some estimates, for every dollar that is used to purchase bitcoin, its price goes up between $20 and $1001. I’d argue that, if the Fed were the buyer, we would easily be at the top of that range. In fact, a Fed announcement that it’s even thinking about Bitcoin QE would probably produce the desired wealth effect without injecting any money. A study in 2019 concluded that, for stocks, each dollar of wealth created resulted in 2.8 cents worth of spending.2 Doing some quick math, that means every $1 the Fed spends on Bitcoin QE produces $100 in wealth, which results in $2.80 worth of spending. Helicopter money achieved, with a money multiplier. These are rough estimates for sure, but you get the picture.

A logical question here is, why does the size of the Fed balance sheet even matter? After all, if the Fed wants to inject more stimulus, it has the means to buy all the bonds available and pump risk asset prices indirectly. There are several potential problems with this. First, the size of the Fed balance sheet is already massive. I think even Fed officials would admit what they have done is unprecedented and experimental, and there may be risks associated with a large balance sheet that aren’t apparent.

Second, by pumping banks full of reserves, the unsecured interbank lending market is dying. Some have even speculated that it doesn’t make sense for the Fed to target the federal funds rate anymore, as most of the lending between banks is now secured. This is a potential problem because, aside from regulators, banks effectively police themselves when lending unsecured to each other. If Bank A is lending unsecured to Bank B, you’d best believe that Bank A has done some homework to ensure Bank B is solvent. For this reason, the lack of interbank lending may be increasing systemic risk.

Third, regulations (such as the supplementary leverage ratio) limit the size of large bank balance sheets. Some of them are essentially choking on reserves, and offloading them for treasuries through reverse repo. That raises the question, how much more bond QE can the system take? It seems more prudent to inject fewer reserves, with a bigger bang for the buck, than to inject more reserves, with a small effect.

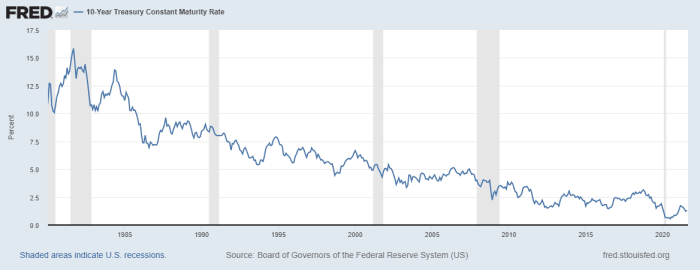

Some will argue that pumping bitcoin is morally unfair, in that it directly enriches bitcoin holders, whereas targeting interest rates to stimulate asset prices works more broadly. But let’s look at past beneficiaries of Fed policies. In the 1970s, the Greatest Generation benefited from holding gold during a period of high inflation, enabled by dovish Fed policy. During the 1980s and through today, boomers have benefited from decades of falling interest rates (see below), which have resulted in massive wealth effects for them due to decades of higher prices for bonds, real estate, and equities. Today, millennials are faced with higher home prices and an explosion of student loan debt. Given that estimates show that almost 50% of bitcoin owners are millennials,3 would Bitcoin QE really be that unfair? After all, the Fed has in the past embarked on targeted policies that directly benefited junk bond holders, home owners, and large banks, and recently it’s been considering the impacts of Fed policy on minorities. Politicians are aware of the problem, as we are even seeing proposals to wipe out student loans. Is that fair to someone who paid off their student loans themself? Seems to me, it would be equally as fair to reward millennials who attempted to save and invest. I would call Bitcoin QE a way to restore generational karma.

There would be other effects that could prove desirable. Immediately after the Fed announced it would be purchasing bitcoin, many of the remaining tens of millions of Americans who don’t own any would scramble to get some. Thus, with nearly everyone owning a digital wallet, it becomes a way for the Fed to raise the price of an asset that is directly owned by individuals. While this may change eventually, as of right now, most institutions haven’t bought bitcoin en masse because of various regulatory constraints around custody and reporting. That means that Bitcoin QE could be the closest we get to QE for the people. And would it really be so bad if bitcoin got more Americans to start investing? Clearly it has that effect on young people.

The last primary reason for the Fed to buy bitcoin is to get ahead of the global adoption curve. Bitcoin is the largest and most secure decentralized digital currency on the planet. We are already seeing small countries like El Salvador adopting bitcoin as a national currency, and others contemplating it. Compared to the global banking system, it’s a faster and cheaper means to move money. In addition, there has been growing chatter about de-dollarizing global trade. Back before the Chinese digital yuan project took center stage, there was talk of creating a global currency like the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights, which is essentially a basket of global currencies. This sentiment is precisely what Facebook was tapping into with its now-failed Libra project. The governments of the world uniformly and effectively squashed the idea. If something were to replace the U.S. dollar for global trade, no one wants a centralized player like Facebook or China running the show. Given all this, it makes sense that, if the United States wishes to remain at the top of the global banking pyramid, it should be hedging its risk by acquiring any potential replacement currency – and that means acquiring at least some Bitcoin.

So when can we realistically expect the Fed to consider Bitcoin QE? Uhh… don’t hold your breath. Aside from the political firestorm such a policy would create, there are many reasons implementation would be difficult. For starters, changes in Fed policy mostly move at a snail’s pace. Pivots are well telegraphed through Fed communications, which is evident from past Powell-speak about “not even thinking about thinking about removing accommodation.” And that’s just operating within their existing framework; more structural policy changes like transitioning to average inflation targeting, or even common-sense changes like converting to a Nominal Gross Domestic Product target, take years, or even decades, of Fed study and analysis. The Fed is an extremely conservative institution.

Then there is the Fed’s role as a banker to banks. The Fed has a balance sheet like any other bank, with profits and losses being ultimately remitted to the U.S. Treasury. Any losses from Bitcoin QE would therefore have the appearance of being borne by U.S. taxpayers, even if such accounting is really just a mirage. It sounds silly that an institution with the statutory authority to create trillions in liquidity should have any questions about solvency or losses, but these accounting perceptions matter.

Last, and most importantly, the Fed is restricted by law in regard to which assets it can buy. Probably the most common interpretation is that the Fed can’t even buy equities. Although, it’s worth noting that at one time, many didn’t believe the Fed could legally buy mortgage-backed securities or corporate junk bonds. Yet, during a crisis, the Fed can get creative. So maybe, just maybe, if we encountered a perfect economic storm, the Fed could employ some legal loophole for Bitcoin QE.

So where does that leave us? Well, I’ve argued here there is a case to be made for Bitcoin QE. And to be clear, I’m not advocating ALL QE go into bitcoin. A reasonable QE “bang for your buck” strategy for the Fed would be to buy a lot of long-dated government bonds, some corporates, some stocks, and a little bitcoin. Unfortunately for Bitcoiners, given the political and statutory realities, I’m not optimistic we could see a policy shift any time soon. Most likely, it would take amending the laws that govern the Fed. And there are many other angles to this, such as where and how the Fed enters private markets to purchase bitcoin as well as the potential benefits/drawbacks of dollar devaluation.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of this thought experiment. Indeed, a full analysis of the implications and operational constraints of Bitcoin QE would likely require a myriad of academic papers and years of Fed debate before implementation. It goes without saying that no one at the Fed is going to accept these back of the envelope estimates on the wealth effects, spending estimates, and the beneficiaries of such a large policy shift. At the current pace of legislative and Fed policy, we might well see millennials retiring before we see Bitcoin QE. All that said, my aim here is to get the ball rolling and start the discussion. It’s been said that the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. I say, there are some potential benefits to Bitcoin QE, so let’s start walking.

Follow me on twitter at @monetarywonk

1 https://cointelegraph.com/news/1-trillion-is-a-conservative-market-cap-for-bitcoin-said-investment-cio

2 https://www.nber.org/digest/aug19/new-estimates-stock-market-wealth-effect#:~:text=County%2Dlevel%20data%20on%20U.S.,which%20raises%20employment%20and%20wages.&text=Nenov%2C%20and%20Alp%20Simsek%20find,by%202.8%20cents%20per%20year.

3 https://bitcoinist.com/google-analytics-bitcoin-demographics/

This is a guest post by Monetary Wonk. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.

Comments (No)